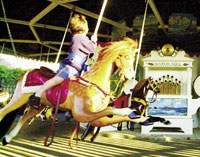

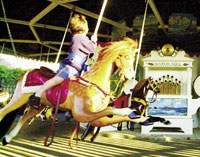

The carousel is unique in that its horses are not attached to the floor, but hang by chains suspended by overhead "sweeps". The faster the ride, the farther out the horses swing, hence the name "Flying Horse Carousel." Unlike most carousels, there is no wooden platform. The horses, smaller than most, "fly" out over a dirt floor. Their tails and manes are made of real horsehair, the saddles are genuine leather, and the horses possess their original agate eyes. Each horse is hand-carved from a single piece of wood. The Flying Horse Carousel progressed from its original means of propulsion "horsepower" to water power and finally, to electricity. Riders are limited to children under 12 years of age.

The Flying Horse Carousel is believed to be the oldest carousel in America. The date of construction of the Watch Hill carousel is uncertain, however it was probably manufactured by the Charles W. Dare Company of New York in 1876 and possibly as early as 1867.

By Memorial Day, however, the town part of Westerly (pop. 23,000) has undergone its annual metamorphosis. Cars line the streets, and customers queue up for homemade ice cream at St. Claire's Annex, listening to the music of seagulls and the Flying Horses Carousel a few steps away. The 20 primitive wooden horses created by carousel-maker Charles Dare after the Civil War have been taken from storage and hung on their chains, so yet another generation of children can lean from the leather saddles to reach for the brass ring.

On a hill above the Atlantic stands a group of weathered mansions where the likes of Frank Sinatra, David Niven, and Clark Gable vacationed in years past. A sea breeze sweeps along the main street past a row of shops and among them the 85-year-old Olympia Tea Room, where patrons fill sidewalk tables, and the Book and Tackle, its books lining shelves outside the door.

As so often happens, the Flying Horses have attracted the attention of a carload of visitors, who pull to the curb for a better look. Jack Blinn and his brother, Robert, have brought their 103-year-old mother, Margaret, to see the carousel. It holds memories for them all.

"When I was 16, I worked here parking cars," says Blinn, a Westerly native now living in San Antonio, Texas. "That was 1951." The carousel has served four generations of Blinns, from Margaret to her great-grandchildren in nearby Groton, Conn., a claim that would raise no eyebrows in Watch Hill, where the carousel and the oldest continuously operating one in the country is a great source of pride.

"One fall a couple came here from the Midwest just to see the horses and they'd already been put away," recalls resident Pat Richins. "They were shattered. People have such strong feelings about them."

Left here by gypsies in 1888, the carousel survived the 1938 hurricane that wiped Napatree Point clean of houses and claimed more than 50 lives. Following the storm, the horses were dug from the sand and the carousel put back to work. The homes, however, were never rebuilt and the point became a conservation area where piping plovers and ospreys nest.

Over the years, salt and wind-driven sand took their toll on the carousel. The late Harriet Moore, through the Watch Hill Improvement Society, launched a maintenance program that's continued to this day. In 1993, woodcarver Gary Anderson of nearby Pawcatuk, Conn., stripped the horses of some 50 layers of paint before reaching bare wood. After filling divots, he repainted and varnished them and replaced cracked leather saddles and horsehair manes shortened by nest-building birds. The stripping revealed the horses were hollow, modeled after early "safety" rocking horses. "At first, I thought they should be in a museum," says Anderson, "but the people of Watch Hill felt it was important to have them out for kids to ride."

Stories about the carousel abound. One tells of an old horse that powered the carousel by pulling on a line. When the horse died, the hair from its tail was used on one of the wooden horses, Anderson says.

Watch Hill has been called timeless a fitting description in light of the unchanging mansions, lovingly maintained carousel, and a lighthouse townspeople took over when the Coast Guard decommissioned it. But while the easy-going pace of a seaside village perseveres, change can be found. Eight grand hotels once lured summer visitors here: now only the Watch Hill Inn and Ocean House remain and the latter is planned for subdivision. Increasing numbers of the town's summer population are becoming year-round residents.

Realtor Bob Richins, a former carousel committee member, foresees a time when the horses will have to be replaced and the originals put on display. Until then, however, children ride the Charles Dare originals and visitors share memories of long-ago rides. "It's important to the town that things of significance be maintained," Richins says. "It's just a very caring citizenry."