The line from Aurora to Chicago was built through the fledgling towns of Naperville, Lisle, Downers Grove, Hinsdale, Berwyn, and the west side of Chicago. It was opened in 1864, and passenger and freight service began. Regular commuter train service started in 1864 and remains operational to this day, making it the oldest surviving regular passenger service in Chicago. Both the original Chicago line, and to a much lesser extent, the old Aurora Branch right of way, are still in regular use today by the Burlington's present successor BNSF Railway.

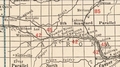

The company was renamed Chicago and Aurora Railroad on June 22, 1852, and given expanded powers to extend from Aurora to a point north of LaSalle; this extension, to Mendota, was completed on October 20, 1853. Another amendment, passed February 28, 1854, authorized the company to build east from Aurora to Chicago via Naperville, and changed its name to Chicago and Southwestern Railroad. The latter provision was never acted upon, and was repealed by an act of February 14, 1855, which instead reorganized the line as the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad.

With a steady acquisition of locomotives, cars, equipment, and trackage, the Burlington Route was able to enter the trade markets in 1862. From that year to date, the railroad and its successors have paid dividends continuously, and never run into debt or defaulted on a loan—the only Class I U.S. railroad for which this is true.

After extensive trackwork was planned, the Aurora Branch changed its name to the Chicago and Aurora Railroad in June 1852, and to Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad in 1856, and shortly reached its two other namesake cities, Burlington, Iowa and Quincy, Illinois. In 1868 CB&Q completed bridges over the Mississippi River both at Burlington, Iowa, and Quincy, Illinois giving the railroad through connections with the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad (B&MR) in Iowa and the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad (H&StJ) in Missouri. In 1860 the H&SJ carried the mail to the Pony Express upon reaching the Missouri River at St. Joseph, Missouri. In 1862 The first Railway Post Office was inaugurated on the H&StJ to sort mail on the trains way across Missouri.

The B&MR continued building west into Nebraska as a separate company, the Burlington & Missouri River Rail Road, founded in 1869. During the summer of 1870 it reached Lincoln, the newly designated capital of Nebraska and by 1872 it reached Kearney, Nebraska. That same year the B&MR across Iowa was absorbed by the CB&Q. By the time the Missouri River bridge at Plattsmouth, Nebraska was completed the B&MR in Nebraska was well on its way to the Mile High city of Denver, Colorado. That same year, the Nebraska B&MR was purchased by the CB&Q, which completed the line to Denver by 1882.

Ultimately, Perkins believed the Burlington Railroad must be included into a powerful transcontinental system. Though the railroad stretched as far west as Denver and Billings, Montana, it had failed to reach the Pacific Coast during the 1880s and 1890s, when construction was less expensive. Though approached by E. H. Harriman of the Union Pacific Railroad, Perkins felt his railroad was a more natural fit with James J. Hill's Great Northern Railway. With its river line to the Twin Cities, the Burlington Route formed a natural connection between Hill's home town (and headquarters) of St. Paul, Minnesota, and the railroad hub of Chicago. Moreover, Hill was willing to meet Perkins ' $200-a-share asking price for the Burlington's stock'. By 1900, Hill's Great Northern, in conjunction with the Northern Pacific Railway, held nearly 100 percent of Burlington's stock.

In 1901, a rebuffed Harriman tried to gain an indirect influence over the Burlington by launching a stock raid on the Northern Pacific. Though Hill managed to fend off this attack on his nascent system, it led to the creation of the Northern Securities Company, and later, the Northern Securities Co. v. United States ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The only major strike in the line's history came in 1888, the Burlington railway strike of 1888. Unlike most strikes, which were based on unskilled workers, this one was based on the highly skilled well-paid engineers and firemen, a challenge to management prerogatives. A settlement would have been much cheaper, but President Perkins was determined to assert ownership rights and destroy the union threat. The fight dragged on 10 months before the financially and emotionally exhausted strikers finally gave up, and Perkins declared a total victory. However, he had spent heavily on strikebreakers, lawsuits, and police protection, hurting the balance sheets and putting the railroad in a poor position to face the nationwide depression of the Panic of 1893.

In 1929, the CB&Q created a subsidiary, the Burlington Transportation Company, to operate intercity buses in tandem with its railway network. In 1936, the company would become one of the founding members of the Trailways Transportation System, and still provides intercity service to this day as Burlington Trailways.

As early as 1897, the railroad had been interested in alternatives to steam power, namely, internal-combustion engines. The railroad's shops in Aurora had built an unreliable three-horsepower distillate motor in that year, but it was hugely impractical (requiring a massive 6,000-pound flywheel) and had issues with overheating (even with the best metals of the day, its cylinder heads and liners would warp and melt in a matter of minutes) and was therefore impractical. Diesel engines of that era were obese, stationary monsters and were best suited for low-speed, continuous operation. None of that would do in a railroad locomotive; however, there was no diesel engine suitable for that purpose then.

Always innovating, the railroad both purchased "doodlebug" gas-electric combine cars from Electro-Motive Corporation and built their own, sending them out to do the jobs of a steam locomotive and a single car. With good success in that field, and after having purchased and tried a pair of General Electric steeple-cab switchers powered by distillate engines, Burlington president Ralph Budd requested of the Winton Engine Company a light, powerful diesel engine that could stand the rigors of continuous, unattended daily service.

The experiences of developing these engines can be summed up shortly by General Motors Research vice-president Charles Kettering: "I do not recall any trouble with the dip stick." Ralph Budd, accused of gambling on diesel power, chirped that "I knew that the GM people were going to see the program through to the very end. Actually, I wasn't taking a gamble at all." The manifestation of this gamble was the eight-cylinder Winton 8-201A diesel, a creature no larger than a small Dumpster, that powered the Burlington Zephyr (built 1934) on its record run and opened the door for developing the long line of diesel engines that has powered Electro-Motive locomotives for the past seventy years.

The Burlington railroad was owned by the Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroads. As early as 1960 the three railroads were planning on merging into one. A proposed name for the merger was "The Great Northern, Pacific and Burlington lines".

As the financial situation of American railroading continued to decline through the 1960s, forcing restructuring across the country, the Burlington Railroad merged with the Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle railroads on March 2, 1970 to form the Burlington Northern (26 years later, the BN and Santa Fe Railroads merged to become BNSF). Passenger service was markedly reduced, as people had shifted to using private automobiles for many trips.

The Zephyr fleet included:

Pioneer Zephyr (Lincoln-Omaha-Kansas City)

Twin Cities Zephyr (Chicago-Minneapolis-St. Paul)

Mark Twain Zephyr (St. Louis-Burlington)

Denver Zephyr (Chicago-Denver)

Nebraska Zephyr (Chicago-Lincoln)

Sam Houston Zephyr (Houston-Dallas-Ft. Worth

Ozark State Zephyr (Kansas City-St. Louis)

General Pershing Zephyr (Kansas City-St. Louis)

Silver Streak Zephyr (Kansas City-Omaha-Lincoln)

Ak-Sar-Ben Zephyr (Kansas City-Omaha-Lincoln)

Zephyr Rocket (St. Louis-Burlington-Minneapolis-St. Paul), jointly with Rock Island

Texas Zephyr (Denver-Dallas-Ft. Worth)

American Royal Zephyr (Chicago-Kansas City)

Kansas City Zephyr (Chicago-Kansas City)

California Zephyr (Chicago-Oakland): Chicago-Denver handled by CB&Q; Denver-Salt Lake City by Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad; Salt Lake City-Oakland by Western Pacific Railroad

Other named passenger trains which operated on the Burlington included: These trains were operated jointly with Northern Pacific Railway and had a different name when they were east or westbound.

The club car of the Chicago Limited and the Denver Limited. The train had an eastbound and westbound name.

Adventureland (Kansas City-Billings)

Aristocrat (Chicago-Denver): replaced the Colorado Limited

Ak-Sar-Ben (Chicago-Lincoln): replaced Nebraska Limited and replaced by Ak-Sar-Ben Zephyr

American Royal (Chicago-Kansas City): replaced by the American Royal Zephyr.

Atlantic Express (Seattle-Tacoma-Chicago): jointly with Northern Pacific Railway

Black Hawk (Chicago-Twin Cities overnight)

Buffalo Bill (Denver-Yellowstone) Seasonal tri-weekly service between Denver, Colorado and Yellowstone National Park via Cody.

Wyoming

Chicago Limited (Chicago-Denver)

Coloradoan (Chicago-Denver): replaced by the Aristocrat

Denver Limited (Denver-Chicago)

Exposition Flyer (Chicago-Oakland) in conjunction with D&RGW and WP before the launching of the California Zephyr.

Empire Builder: handled Great Northern Railway's flagship between Chicago and Minneapolis

Fast Mail (Chicago-Lincoln)

Mainstreeter: handled the Northern Pacific Railway's secondary transcontinental between Chicago and Minneapolis

Nebraska Limited (Chicago-Lincoln): replaced by the Ak-Sar-Ben

North Coast Limited: handled Northern Pacific Railway's flagship between Chicago and Minneapolis

North Pacific Express (Chicago-Seattle-Tacoma): jointly with Northern Pacific Railway

Overland Express (Chicago-Denver). This train, along with The Aristocrat and the Colorado Limited, were promoted as companion trains to the streamlined Denver Zephyr

Shoshone: (Denver-Billings) operated between Denver, Colorado and Billings, Montana, referred to affectionately as "The Night Crawler"

Western Star: handled the Great Northern Railway's secondary transcontinental between Chicago and Minneapolis

Zephyr Connection: (Denver-Cheyenne) offered daytime service along Colorado's Front Range between Denver, Colorado and Cheyenne,

Wyoming

The California Zephyr is still operated daily today by Amtrak as trains Five (westbound) and Six (eastbound). Another Amtrak train, the Illinois Zephyr, is a modern descendant of the Kansas City Zephyr and the American Royal Zephyr services.

The Burlington was a leader in innovation; among its firsts were use of the printing telegraph (1910), train radio communications (1915), streamlined passenger diesel power (1934) and vista-dome coaches (1945). In 1927, the railroad was one of the first to use Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) and by the end of 1957 had equipped 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of its line.

The railroad had one of the first hump classification yards at its Cicero Avenue Yard in Chicago, allowing an operator in a tower to line switches remotely and allowing around-the-clock classification.